I joined my first fiction critique group in the early 80s, and I’ve been in and out of critique groups since.  Being in a critique group involves reading and evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the group members’ short stories to help move them toward publication.

Being in a critique group involves reading and evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the group members’ short stories to help move them toward publication.

I also served as the fiction editor for The California Quarterly, the literary magazine for the University of California at Davis where I spent two years reading the slush pile (all the submitted manuscripts), choosing stories for the magazine. I edited a horror/crime anthology, which also meant reading a slush pile. I’ve taught numerous workshops in fiction writing and read hundreds of students’ short stories and novels in the classes I’ve taught.

In other words, I’ve spent much of the last forty years or so figuring out what makes a story stand out.

What makes that one story out of a hundred stronger and more interesting than the other ninety-nine?

This year I’m the managing editor for Western Colorado Voices, an anthology of fiction, poetry, and creative non-fiction essays coming from the Western Colorado Writers Forum. Once again, I’ll be reading stories and trying to find the very best for publication.

Are you interested in producing publishable fiction?

Whether you’re writing for the anthology the WCWF is producing, or working on projects for other venues, I’d like to share what I’ve learned.

Here’s what I’m looking for:

- Competent, confident writing. This is language that does not hesitate. In general, it’s language built on well-chosen action verbs with varied sentence lengths and types. It doesn’t accidentally repeat the same sentence beginnings or the same word too close to itself. It has a rhythm that doesn’t trip itself or make me reread to figure out what is going on. Pronoun references are clear, paragraphing aids in clarity, and the words are the right words. Of all the elements I want to see in a story, this is the one that is the most irreplaceable. Competent writing is what editors look for when they pull a manuscript only halfway out of its submission envelope. If the writing betrays a lack of competence in the first half page, there’s no point in reading anymore. Nothing will save it.

- Strong beginning: There needs to be something arresting fairly early in a piece. I can be patient for a while, particularly if the language is nicely done, but even then, at some point I’m going to start to wonder why I’m there. What I need is two-fold: an event or conversation or description that tells me something important is happening in the world of the characters; and I need to feel I’m in the hands of someone who knows the end of the story. This may be because of my strongly held belief that the beginning exists to set up the end. The beginning is the first rhetorical shot the author takes. It’s a move, like in chess. It’s a strategy shoving the reader in a direction. Too many stories don’t appear to be written with the ending in mind. The beginning doesn’t feel like a confident first step in a direction.

- A sense of the conflict. I need to know early in the story what the character wants, what stands in the way, and what is at stake. Sometimes this is obvious; sometimes it doesn’t focus until the end, but there should be a sense of urgency. The events have to feel like they matter to the point of view character or to the storyteller. Some stories are like a war, and there are opposing sides. I want to know who the combatants are and what condition would constitute a win or a loss for each. Some stories are journeys: there needs to be, then, a clear sense of where we are going and why it’s important to get there. Some stories are a birth. At the end, something will be born that didn’t exist before. In this kind of story, I may not get an immediate sense of direction, but I should feel characters under stress early in the story so I know that change is on the horizon. Occasionally, stories are a riddle or puzzle. The early events or the character’s situation are described in such a way that I want to know what happened to produce this condition. The payoff in the end is a satisfying explanation for the initial situation. I find puzzle stories the hardest to do well, by the way, and the kind of story I see way too often in workshops.

- “Gems” on the page. These are clever, interesting, arresting elements that even if I don’t know what is going on, or I don’t like what I’m reading in general, I recognize are cool. It might be a turn of phrase, a line of dialogue, a funny bit, a place name, an aphorism, or a touch (or bucket) of figurative language. The gem is evidence of the writer caring not only about the big picture but also the details and style along the way.

- A sense of place. Every scene requires enough information so that I know where the characters are, where they are in relationship with each other, and how the point of view character is experiencing the environment. Early scenes probably need more setting than later ones, but there’s a lot of flexibility in presentation as long as I have the essential questions answered in my mind: Where are we? Who is in the scene? Where are they in relation to each other?

- Characters who are fleshed out enough that I care about their fates. Sometimes I care about a character just because they have a cool voice or an identifiable attitude. Sometimes it’s because of actions they take. Most often character comes out of a point of view that reflects who they are. Does their point of view color the world of the story? In most stories, if I don’t know the character well enough to care, then what happens to them won’t matter. In some stories, what happens is what is most interesting, and the characters are less important, but these are rare stories. Plot will occasionally be the star in a story, but strong characters save a plot way more often than strong plot saves the characters.

- Active characters who struggle. The struggle is what makes them interesting. The main character should be an active participant in her/his story. Even if they don’t know what is going on in the story, and events are motivated by outside agencies, the character should be trying to survive, trying to get ahead of events to control what is happening. I look for active characters who are not merely passive victims. Characters don’t have to win, but they shouldn’t lose because they didn’t move. The actors must act.

- An ending that resonates. It’s not just that the plot ends and the conflict is resolved, but that the story feels like it has been told to illuminate some mystery of existence. This is a fancy way of saying there should be thematic overtones in the end. The storyteller told the story because she/he thought the tale was interesting, and what makes it interesting is that it is a revelation. It uncovers, even a little, the mysteries of the human condition, or it tells us something important about the universe we live in, or it challenges our complacency or apathy about life. The ending should feel larger than the whole, like a poem. I should finish with a rueful grin of recognition because the writer shared a truth that I hadn’t thought about before, or I should feel an empathetic spark for the characters because they went to a place or completed a cycle that I now understand because I read their story. The end of the story answers the question of “so what?” It’s the reason the story was written in the first place. All the good writing before the ending should be fun or provocative or interesting or amusing, and good writing is a kind of payoff on its own—after all, the journey needs to be worthy—but everything in the story exists to make the end work.

There has to be a good ending.

###

When I started reading fiction for The California Quarterly, I’d take the pile of manuscripts that came in for the week to the student union to read them. At first, I didn’t know what to look for. I was a new editor! But after I’d read for a few weeks I learned several things. Here are four of them:

1st – Some stories made moves I didn’t like that I realized were features of my own stories. Reading slush made me a better writer.

2nd – Most of the stories weren’t terrible (but there were a few). Most were readable stories written by people who clearly knew what a story was. The problem those stories had was they weren’t great. I wasn’t searching for competently told fiction. I wanted the best. The quickest way for most writers to learn this is to read slush, or read entries to a contest, or be a part of a writing group. Remember, editing for an anthology is essentially a sorting process. Imagine a stack of all the stories submitted to the editor. At first, there are only two stories. The editor reads both and decides which is stronger and a better fit for the project. That’s the beginning of the stack. Each manuscript after those first two are sorted into the stack until after all the manuscripts are read, the stories on top make it into the anthology. The writers’ job is to write the best story they can. The editor’s job is to sort them all out.

3rd – I grew impatient with cliches (both in wording and situation), and clunky prose.

4th – The best stories stood out with what felt to me to be an obvious glow. I found myself in the student union reading story after story, knowing they were okay, generally, but not special. Then I would read the first paragraph of the next manuscript, and something about it would catch me. I’d want to grab a random person from a table near to me so I could read the first few sentences to them. “This is so good!” I’d say.

###

I’ve included quite a bit in this blog entry that has grown pretty long.

Remember that editing is a subjective process.

I’m just one editor, and I take my judgments to the slush pile. A rejection from me just means that your story at this moment, for this editor, didn’t make the cut. Another editor could very well accept your piece. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter manuscript was rejected by the first twelve publishers to see it. Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind was rejected by forty publishers. Stephen King’s first novel, Carrie, was rejected eighty times.

For myself as a writer, I have posted above my workstation a quote from the comedian, Steve Martin. He said, “Be so good they can’t ignore you.” I contemplate that often.

I wish you the best of luck in your journey towards publication.

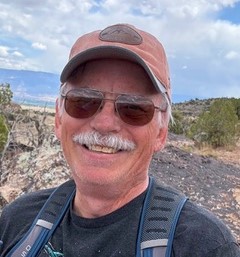

James Van Pelt has been selling short fiction to many of the major venues since 1989. Recently he retired from teaching high school English after thirty-seven years in the classroom. He has been a finalist for the Nebula, the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award, Locus Awards, and Analog and Asimov’s reader’s choice awards. Years and years ago he was a finalist for the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. He still feels “new.” Fairwood Press recently released a huge, limited-edition, signed and numbered collection of his work, THE BEST OF JAMES VAN PELT. He can be found online at his website or on Facebook.

James Van Pelt has been selling short fiction to many of the major venues since 1989. Recently he retired from teaching high school English after thirty-seven years in the classroom. He has been a finalist for the Nebula, the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award, Locus Awards, and Analog and Asimov’s reader’s choice awards. Years and years ago he was a finalist for the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. He still feels “new.” Fairwood Press recently released a huge, limited-edition, signed and numbered collection of his work, THE BEST OF JAMES VAN PELT. He can be found online at his website or on Facebook.

You can’t help but learn something when James goes to such an effort to instruct new, inexperienced writers, such as myself. Thank you for taking on this BLOG. I wait for it to hit my inbox and then read and reread it.

Sue B

Hi, Sue. Thanks for the comment.

Thanks, Jim. This is excellent information (as always)!